Surveyed here are two very different, and yet very similar, strains of anarchist organization and propaganda. The first example is the CNT & Anarchist movement in Spain, the latter is the contemporary decentralized global anarchist movement (particularly Western in this focus).

The contemporary anarchist movement is “new” in the key sense that it does not form a continuity with the workers’ and peasants’ anarchist movement of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries – which met its demise under European Bolshevism and Fascism and the American Red Scare. Rather, it represents the revival of anarchist politics over the past decade in the intersection of several other movements, including radical ecology, feminism, black and indigenous liberation, anti-nuclear movements and, most recently, resistance to neoliberal capitalism and the “global permanent war” [1].

Anarchist movements in the early part of the 20th century, such as the CNT and other anarchists in Spain, or the IWW and other labor groups in the United States, learned, organized, and were politically active in ways very different from current anarchist movements. The rise of globalism, technology and access in the latter part of the 20th century, and with it the revival of anarchist politics, is a world very different than the one anarchists in the earlier part of the century found themselves in. Here it will be explored what (perhaps ‘if’) these two periods of anarchist thought share, and how they differ, through the imagery and symbolism they produced.

Anarchism may be the most notorious movement when it comes to propaganda by the deed. That is, anarchists prefer to inspire people by way of example, rather than relying heavily on written discourse or visual propaganda. This has earned the anarchist movement a great deal of negative propaganda by groups seeking to reduce them to nothing more than bomb-throwing social delinquents. For an example of this, watch the videos posted on the Labor Movement Page. Despite this set back, anarchists, for as long as the political theory has existed, have created propaganda to inspire people to their cause.

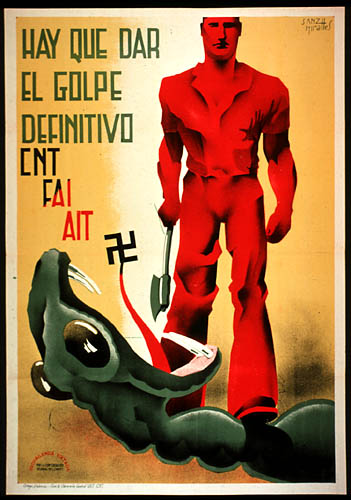

During the Spanish Civil War in the 1930’s anarchists, alongside socialists, communists, and other left groups, fought against the rise of Fascism under General Francisco Franco. Groups like the CNT (Confederación Nacional del Trabajo/National Confederation of Labour), the FAI (Iberian Anarchist Federation), and the AIT (Asociación Internacional de los Trabajadores/International Workers Association) took up arms with the International Brigade and other groups on the side of the Republicans against Franco who lead a military coup of democratic Spain to set up a fascist single-party state. “Anarchists seldom use the phrase ‘civil war’ in relation to the events because it hides the revolutionary nature of the struggle within the republican side, a revolution in which some seven million workers on the land and in industry took over their workplaces” [2]. Indeed, this volatile period in Spain’s history marked a period of two vastly different groups struggling for ideological supremacy. The anarchists of Spain were fighting not only to prevent a fascist Spain, but also to ensure an anarchist commonwealth. The groups fighting against fascism experienced extreme fracture and internal ideological differences, perhaps most notably between the state democrats, the Stalinists, and the anarchists. The CNT and FAI were the largest anarchist organizations, with a combined estimated membership of roughly 60,000. There were also large militias, most notably the Iron Column and Durruti Column (who together made up roughly estimated 40,000 anarchists). These groups, and many like them, created massive amounts of propaganda in the form of posters, as well as texts and other medias.

Propaganda was produced by various oficinas de propaganda to keep morale high for the republican side farmers, soldiers and families as well as hopefully convert a democrat or two. The main themes were anti-fascism, worker solidarity, and liberation. Posters commonly consisted of red and black colors alongside raised fists. This color motif was also used heavily within the IWW and is still used today. Aside from being simply striking, the color black has been a symbol of anarchism since the late 1800’s – as a white flag is the universal symbol for surrender to superior force, the black flag would logically be a symbol of defiance and opposition to surrender. This color black is typically used in a diagonal cut alongside another color representing a variation of anarchism (green-environmental, pink-queer/feminism, etc), the most commonly used color is red for anarcho-syndicalism/communism (the color red is, historically, the color of socialism). Another famous symbol of anarchism, the circle A Ⓐ, representing anarchy and order, was first ever recorded being used by anarchists in the Federal Council of Spain of the International Workers Association. Another common theme was depicting the war as a struggle between man and beast.

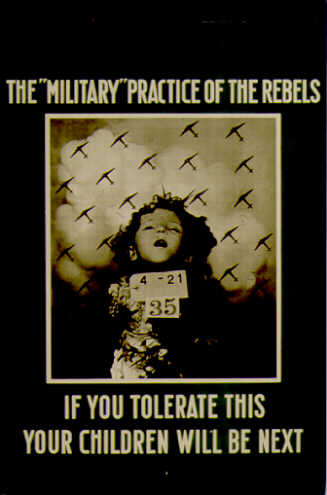

The Republicans also used a very new form of incorporating photographs in their propaganda posters. Typically they would use these photos for shock factor, seeking to show the depravity of the fascists.

Posters were commonly made to inform or suggest action in its viewers. Sometimes it would include a reminder to not steal radios, or to protect farmers’ land, and sometimes it would encourage troops to keep up with studying.

Propaganda films were produced by the Republicans. At the start of the war, filmmaker Luis Buñuel went to Paris following a summons by the Spanish Foreign Ministry to collaborate with the Spanish embassy in Paris in counterespionage and propaganda. Using footage from Spain, Buñuel assembled propaganda films to be consumed by Parisians. Unlike films made for viewing in Spain, these films were targeted audiences in Europe with the objective of changing the doctrine of non-intervention in the war. His most famous film, España, can be found here.

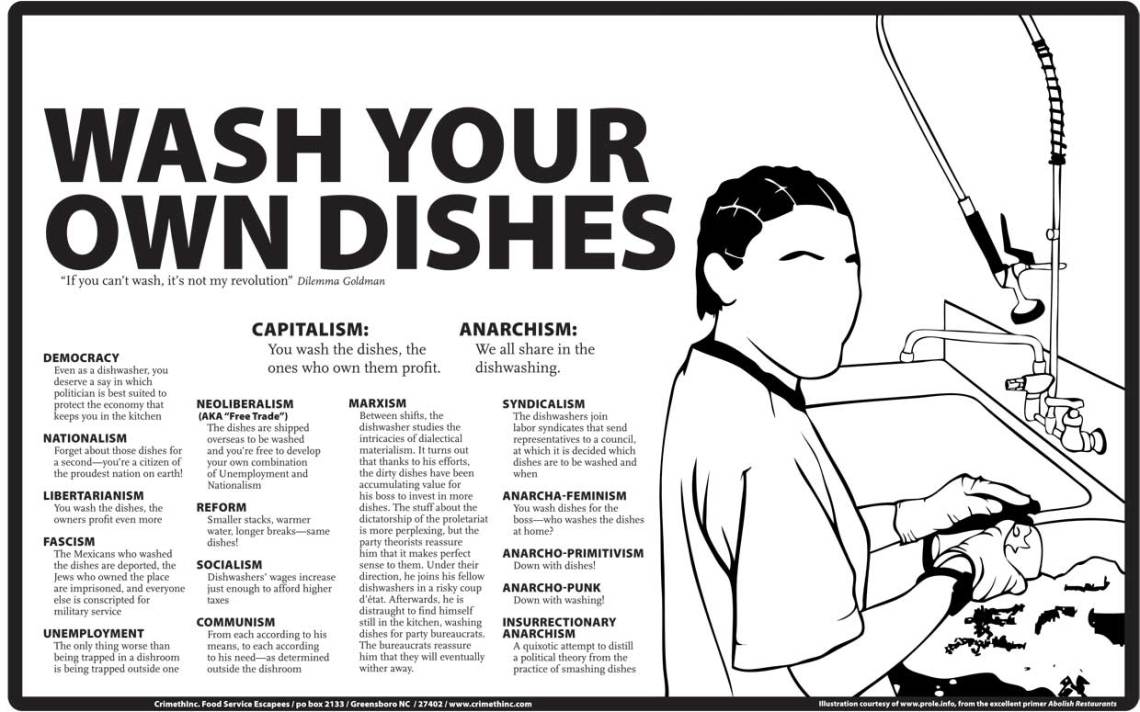

Modern anarchist propaganda is as diverse as the groups who produce it. From groups such as labor unions, action networks and collectives, to more specific and short lived groups borne of struggle anarchists across the globe act and create literature and visual media. Though formally unaffiliated these groups still manage to recognize and identify with each other, based not only on a priori knowledge about a group but on a shared framework of ideas and symbols. The Ⓐ continues to be the most easily recognized symbol of anarchism and alongside it such symbols as the black cross (which represents the elimination of prisons, and support for political prisoners) and the black cat are still used. Contemporary anarchism will still often refer to the same frames as its Spanish and Wobbly predecessors, such as oppression, liberation, and autonomy; anti-capitalist, anti-state.

Contemporary anarchism differs from many historical movements in that it utilizes nearly every conceivable medium for distributing visual propaganda. Rather than simply produce flyers and posters, modern anarchist strains also extensively use such varied vehicles as stickers, banner drops, graffiti, infographics, have an extensive web presence, and, perhaps most uniquely, contemporary anarchists, not unlike how their Spanish predecessors used patches and symbolism for military identification, often incorporate anarchist symbolism via patches into personal fashion for self identification.

CLICK HERE TO VIEW A GALLERY OF ANARCHIST ART

CLICK HERE TO VIEW MORE ABOUT THE IWW

CLICK HERE TO VIEW MORE ABOUT SPAIN

[1] Gordon, Uri. “Anarchism and Political Theory: Contemporary Problems.” Diss. Mansfield College, University of Oxford, 2005. Web. 7 Feb. 2012.

[2]”Anarchism in the Spanish Revolution of 1936.” The Struggle Site. Web. 07 Feb. 2012. <http://struggle.ws/spaindx.html>.

[3] Extensive gallery of Republican propaganda in the Spanish Civil War: http://libraries.ucsd.edu/speccoll/visfront/vizindex.html