From the turn of the century until the mid-1920’s the United States had one of the most thriving periods of organized labor it would ever experience. Labor unions began forming in the United States during the mid-19th century but it wasn’t until the beginning of the 20th century that large and widespread consolidations and growth of membership occurred. During this time there were many labor unions, most small and location or craft based,but two large national unions were central figures of the labor movement and still organize today: The American Federation of Labor (AFL) that was founded in 1886 by an alliance of craft unions disaffected from the Knights of Labor (as it began to fade away) and would eventually become known as the AFL-CIO still active today; and the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) which was founded in Chicago in June 1905 at a convention of two hundred socialists, anarchists, and radical trade unionists from all over the United States (mainly the Western Federation of Miners) who were opposed to the policies of the American Federation of Labor (AFL).

Both unions fought for workers, but in very different style. The AFL focused on higher wages and job security. The AFL, for most of its existence, fought against socialism and the Socialist party and around 1905 it formed alliances with the Democratic party at the local, state and national levels. It primarily organized skilled labor, and was composed primarily of skilled white males. The AFL’s founding convention declared “higher wages and a shorter workday” to be “preliminary steps toward great and accompanying improvements in the condition of the working people” [1]. Leadership within the AFL believed that the expansion of capitalism was the best path to betterment of labor, an orientation which allowed AFL to present itself as the conservative alternative to working class radicalism. The ‘working class radicalism’ it presented itself as an alternative to was the IWW. The IWW’s goal was to promote worker solidarity in the revolutionary struggle to overthrow the employing class in favor of the working class and its motto remains ‘an injury to one is an injury to all’. The IWW saw the AFL as being ineffective at organizing the working class and also saw the AFL as often working in the interest of the owning/employing class, in response the IWW sought to overcome what they saw as a division of the working class by organizing all workers regardless of skill, race, sex, or creed in ‘One Big Union’, this is best reflected in the preamble to the IWW constitution:

The working class and the employing class have nothing in common. There can be no peace so long as hunger and want are found among millions of the working people and the few, who make up the employing class, have all the good things of life. Between these two classes a struggle must go on until the workers of the world organize as a class, take possession of the means of production, abolish the wage system, and live in harmony with the Earth. We find that the centering of the management of industries into fewer and fewer hands makes the trade unions unable to cope with the ever growing power of the employing class. The trade unions foster a state of affairs which allows one set of workers to be pitted against another set of workers in the same industry, thereby helping defeat one another in wage wars. Moreover, the trade unions aid the employing class to mislead the workers into the belief that the working class have interests in common with their employers. These conditions can be changed and the interest of the working class upheld only by an organization formed in such a way that all its members in any one industry, or in all industries if necessary, cease work whenever a strike or lockout is on in any department thereof, thus making an injury to one an injury to all. Instead of the conservative motto, “A fair day’s wage for a fair day’s work,” we must inscribe on our banner the revolutionary watchword, “Abolition of the wage system.” It is the historic mission of the working class to do away with capitalism. The army of production must be organized, not only for everyday struggle with capitalists, but also to carry on production when capitalism shall have been overthrown. By organizing industrially we are forming the structure of the new society within the shell of the old [2].

Both groups experienced extreme member losses in the 1920’s, for some reasons in common as well as some differing. In the teens and twenties the IWW experienced severe political persecution. At the beginning IWW leaders (and members) would be targeted for their radical politics and be accused of crimes, deported, and even killed. Strikes would be violently broken up and individual attacks were common. But it wasn’t until the late teens that attacks on the IWW became widespread and systematic. With the threat of World War I looming, in 1916 the IWW passed a resolution against the war at its convention [3]. The IWW printed anti-war stickers and other various forms of propaganda until Big Bill Haywood, when a declaration of war was passed by the U.S. Congress in April 1917, advised the IWW to begin keeping a low profile. Despite the IWW moderating is public disapproval, the US government used the war as an opportunity to attack the IWW. The Unites States government passed the Espionage Act in 1917, which originally prohibited any attempt to interfere with military operations, to support U.S. enemies during wartime, to promote insubordination in the military, or to interfere with military recruitment. Many saw this as an infringement of free speech, and arrests for one’s beliefs is exactly what occurred. During World War I, the AFL, however, motivated by fear of government repression, had worked out an informal agreement with the United States government, in which the AFL would coordinate with the government both to support the war effort and to join “into an alliance to crush radical labor groups” such as the Industrial Workers of the World and Socialist Party of America [4]. The AFL did not suffer the same persecution that the IWW faced, but in the 1920’s it did experience a dramatic decrease in membership as union repression in general dissuaded public opinion and the open-shop business model became more popular. In the 1940’s, with the passage of the Taft-Hartley Act, both unions would again suffer dramatic membership loss and repression.

The AFL rarely produced propaganda, and sought to maintain an image unaffiliated with politics, though much was produced against them. Throughout these battles that raged between the US government and the IWW a battle of propaganda occurred as well; each group sought public support for their cause (and the denouncement of their opponents) and did so not only in the form of rallies, news, and print but in image as well.

In recruitment efforts, the IWW targeted certain audiences. When addressing a more widespread audience, they targeted the working class, and within the working class they would often target various subgroups, most often according to trade (eg: lumberjacks), sex and race/nationality (eg: Japanese emigrants). Because the IWW’s ideals were so radical they relied heavily on a type of frame alignment known as ‘frame transformation’: this is necessary when the proposed frame “may not resonate with, and on occasion may even appear antithetical to, conventional lifestyles or rituals and extant interpretive frames” [5]. Simply, the ideals and values held by the IWW and the tactics they encouraged were wildly different than how their audience had been interpreting the world – this made frame transformation necessary, and it is typically done in two ways: Domain-specific transformations, such as the attempt to alter the status of groups of people, and global interpretive frame-transformation, where the scope of change seems quite radical—as in a change of world-views, total conversions of thought, or uprooting of everything familiar (for example: moving from market capitalism to communism; religious conversion, etc.) [6]. Essentially, the IWW believed in a specific type of politic known as Solidarity Unionism (some would argue this being the ‘true’ incarnation of anarcho-syndicalism),either way an essential belief within this system is that the working class should control the means of production and do so through unions, labor syndicalism, and direct action, eventually replacing the employing class and capitalism as a whole. The IWW didn’t have the benefit of being able to advertise for the union simply through logo recognition, as the AFL was able to do – the IWW had to link its radical values to the already established working class values and convince them to adopt this new frame (anarcho-syndicalism). They did this using simple slogans, songs, cartoons, and tapping in on what they believed the majority of the working class to be feeling who just didn’t know it yet. They framed concepts such as property and capital as theft, wage labor as slavery, and used virtue words to describe their alternatives – most prominently the concept of ‘solidarity’. “By the accumulated weight of its unceasing propagandistic efforts, and by the influence of its heroic actions on many occasions which were sensationally publicized, the IWW eventually permeated a whole generation of American radicals, of all shades and affiliations, with its concept of industrial unionism as the best form for the organization of workers’ power and its program for a revolutionary settlement of the class struggle” [7].

Both the IWW and the AFL distributed newspapers; the Industrial Worker and the American Federationist, respectively. “The Industrial Worker contained local, state, national, and international news about wobbly strikes and policy and the radical movement in general. About sixty percent focused on news affecting the western states. In addition to news, it contained songs, political cartoons, book reviews, job listings, entertainment and fundraising events, advertisements (in the early days), and notices (mostly personal and union position openings). The paper gives insight into agendas and workings of the I.W.W” [8]. This paper, distributed to members of the union, was also used a tool of spreading information and propaganda to people who were not already in the union, and this is still practice today. Like most politically oriented groups the newsletter served not only the purpose of informing people who were already a part of the group, but also hoped to attract new members, and for this reason the Industrial Worker is of critical importance when surveying their visual propaganda. In nearly every issue, alongside news and other text, logos, union-advertisements, and political cartoons could be found. “Labor cartooning had virtually no traditions behind it when the IWW was founded in 1905, and the Wobblies deserve a large share of credit for developing the new art. Early on, Wob organizers and editors were aware of the propagandistic power of the cartoonist’s art, and many times over the years they actively solicited cartoons from the artists in their ranks. Under the heading ‘Worker needs cartoons’ the Industrial Worker for March 30th, 1918 noted that the paper ‘Desires cartoons on industrial union or revolutionary subjects’ and that ‘cartoons in line with the IWW principles and program are acceptable at all times'” [12].

While the IWW and the AFL were hard at work producing newspapers to make their cause known, so too were mainstream newspapers hard at work to denounce their efforts and dissuade public opinion from supporting unions. Though the IWW, in the coming WWI years, would get the blunt end of the stick, the AFL also received its share of mainstream denouncement in the press.

At the 1916 convention the IWW passed an anti-war resolution:

Anti-war resolution passed by the 1916 convention of the Industrial Workers of the World:

We, the Industrial Workers of the World, in convention assembled, hereby re-affirm our adherence to the principles of industrial unionism, and rededicate ourselves to the unflinching, unfaltering prosecution of the struggle for the abolition of wage slavery and the realization of our ideals in Industrial Democracy.

With the European war for conquest and exploitation raging and destroying our lives, class consciousness and the unity of the workers, and the ever-growing agitation for military preparedness clouding the main issues and delaying the realization of our ultimate aim with patriotic and therefore capitalistic aspirations, we openly declare ourselves the determined opponents of all nationalistic sectionalism, or patriotism, and the militarism preached and supported by our one enemy, the capitalist class.

We condemn all wars, and for the prevention of such, we proclaim the anti-militaristic propaganda in time of peace, thus promoting class solidarity among the workers of the entire world, and, in time of war, the general strike, in all industries.

We extend assurances of both moral and material support to all workers who suffer at the hands of the capitalist class for their adherence to these principles, and call on all workers to unite themselves with us, that the reign of the exploiters may cease, and this earth be made fair through the establishment of industrial democracy. [11]

Proclaim the anti-militaristic propaganda they did in both protest, text and image.

The United States would issue a formal declaration of war in 1917.

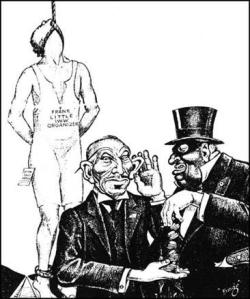

On June 15, 1917, shortly after the U.S. entry into World War I, passed the Espionage Act. It prohibited any attempt to interfere with military operations, to support U.S. enemies during wartime, to promote insubordination in the military, or to interfere with military recruitment. The Unites States used the Espionage Act to launch a red scare resulting in the arrests and deportations of thousands of IWW leaders, organizers and members. On August 1, Frank Little was kidnapped and lynched by masked vigilantes forever sealing his legacy as a martyr. In September 1917, U.S. Department of Justice agents made simultaneous raids on forty-eight IWW meeting halls across the country. In 1917, one hundred and sixty-five IWW leaders were arrested for conspiring to hinder the draft, encourage desertion, and intimidate others in connection with labor disputes; one hundred and one went on trial before Judge Kenesaw Mountain Landis in 1918. “In 1919, 23 states introduced criminal syndicalist laws. Overnight, the IWW found itself liable to prosecution all over the country simply for existing. […] By May 1919, the membership was already down to 30,000” [15]. A wave of such incitement led to vigilante mobs attacking the IWW in many places, and after the war the repression continued. Members of the IWW were prosecuted systematically under various State and federal laws and the 1920 Palmer Raids singled out the foreign-born members of the organization. All of this resulted in the near collapse of the union. The IWW was attacked both in blood and print. The IWW fully acknowledged the targeting of their ranks.

While the US arrested and deported IWW members, they also launched a full scale propaganda attack against them denouncing them as traitors and assisting the Kaiser. In the minds of many Americans, the image of the IWW became inseparable with the image of treason, Bolshevism, Communism and anarchy.

Film propaganda was also produced denouncing the union as “lawless” and “seditious”.

Even Disney would eventually, in 1925, produce a film titled “Alice’s Egg Plant” depicting the union as Bolsheviks. (Though this would not be the last show of Disney’s anti-union sentiment).

Tensions between the IWW and the United States government climaxed in what is now known as the First Red Scare. The first Red Scare began following the Bolshevik Russian Revolution of 1917 and the intensely patriotic years of World War I as anarchist and left-wing political violence and social agitation aggravated national, social, and political tensions. This period was highly xenophobic and generalizing, it was an era that marked little, if any, distinction between anarchism, socialism, communism and social democracy. The press portrayed strikes as radical threats to American society inspired by left-wing, foreign agents provocateur. Thus, the press misrepresented legitimate labor strikes as “crimes against society”, “conspiracies against the government”, and “Plots to establish Communism” [17]. It was during this period that such endearing terms as ‘pinko’ and ‘commie’ would be given derogatory resonance and would be able to be applied to anyone for any political belief that the accuser could equate with dissenting against the United States.

Despite these downfalls the IWW is still alive today, organizing and writing to create a new world within the shell of the old. The IWW’s internationally famous black cat representing sabotage, also known as the ‘wild cat’ or ‘sabot cat’, is still used as a symbol in labor struggles. The term ‘wildcat strike’ refers to this symbol, and, in addition to this, other forms of direct action that were pioneered by the Wobblies are still in use today (such as the slow down strike). An editor for IWW.org writes, “As long as there are workers being exploited, there will always be Wobblies. The IWW never died and it will never die as long as working people are driven like beasts of burden by a few parasites who live off of our labor” [18].

CLICK HERE TO VIEW A GALLERY OF LABOR MOVEMENT ART

CLICK HERE TO VIEW THE PAGE ON THE DISNEY ANIMATORS’ STRIKE OF 1941

[1] American Federation of Labor: History, Encyclopedia, Reference Book. Westport, CT: Greenwood, 1977. 6. Print.

[2] Chicago, IWW. “Preamble to the IWW Constitution.” Industrial Workers of the World: One Big Union! IWW, 5 Jan. 2005. Web. 07 Feb. 2012.

[3] Peter Carlson, Roughneck: The Life and Times of Big Bill Haywood (1983), pages 241.

[4] Goldstein, Robert Justin (2001). Political Repression in Modern America. University of Illinois Press. p. 121.

[5] Snow, David A., R. Burke Rochford, Jr., Steven K. Worden, and Robert D. Benford. 1986. “Frame Alignment Processes, Micromobilization, and Movement Participation.” American Sociological Review 51: 473.

[6] Snow, David A., R. Burke Rochford, Jr., Steven K. Worden, and Robert D. Benford. 1986. “Frame Alignment Processes, Micromobilization, and Movement Participation.” American Sociological Review 51: 474

[7] Cannon, James P. “The I.W.W.” Marxists Internet Archive. Fourth International, 1955. Web. 07 Feb. 2012. < http://www.marxists.org/archive/cannon/works/1955/iww.htm >.

[8] Thorpe, Victoria, and Chris Perry. “Industrial Worker.” Labor Press Project. University of Washington Pacific Northwest Labor and Civil Rights Projects. Web. 7 Feb. 2012. < http://depts.washington.edu/labhist/laborpress/Industrial_Worker.htm >.

[9] The American employer, Volumes 1-2, American Employer Pub. Co., Chamber of Commerce Building, Cleveland, Ohio, December, 1913, page 283

[10] Clubb, John Scott. “The Unemployed.” Cartoon. The Rochester Herald 10 Mar. 1914. Library of Congress ed., Prints & Photographs Online Catalog. <http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2009616454/>

[11] IWW.org Editor. “The IWW Position on War.” Industrial Workers of the World: One Big Union! IWW, 1 Jan. 2012. Web. 7 Feb. 2012.

[12] Rebel Voices: An IWW Anthology. Ed. Joyce L. Kornbluh. Comp. Fred Thompson and Franklin Rosemont. Oakland, CA: PM, 2011. 425-26. Print.

[13] “Little, Frank: IWW Organizer.” The Bisbee Deportation of 1917. University of Arizona, 2005. Web. 07 Feb. 2012. < http://www.library.arizona.edu/exhibits/bisbee/history/whoswho/frank_little.html >

[14] Rebel Voices: An IWW Anthology. Ed. Joyce L. Kornbluh. Comp. Fred Thompson and Franklin Rosemont. Oakland, CA: PM, 2011. 312. Print.

[15] Steven. “1905-Today: The Industrial Workers of the World in the US.” Libcom.org. 17 Sept. 2006. Web. 07 Feb. 2012. < http://libcom.org/history/articles/iww-usa >.

[16] Rogers, W.A. “To Make America Safe for Democracy.” Cartoon. The New York Herald 17 Oct. 1919, pg. 3. Library of Congress ed., Prints & Photographs Online Catalog. <http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2010717816/>

[17] Political Hysteria in America: The Democratic Capacity for Repression 1971, p. 31.

[18] IWW.org Editor. “The Modern Relevance of the IWW.” Industrial Workers of the World: One Big Union! IWW, 8 Nov. 2011. Web. 07 Feb. 2012.